The Case of Pratul Dash

A Living Space (Details) Acrylic on Canvas, Trypitch, 2008

Dr. Rajesh K Singh

The aim of this article is threefold. One, to formulate a basis for evaluating contemporary art in India; two, based on the formulation, evaluate the place of young contemporaries from Orissa; and three, to discuss the synchronic and diachronic axis of the art of Pratul Dash. For these aims, ascertaining of aesthetic and historical parameters would be necessary, since none exist readymade. The parameters of evaluating the Indian modern would come from a glance at the history of modern Indian art in general, and of the dominant forces, objectives, currents, and sentiments in particular. Also, an overview of modern art in Orissa—where Pratul hails from—may help in knowing what intervention has been made by Orissa in the mainstream art scenario. Lastly, some works of the artist will be examined to evaluate their contextual mapping and identity in the linguistic and conceptual framework of contemporary Indian art.

20th century Indian art—the turning points

The economic ‘liberalization’ of India starting around 1993 engendered heightened cultural interactions of India with the world changing radically the way art is produced, displayed, and disseminated. The change coming in the early 1990s is marked by the emergence of ‘alternative’ and experimental art practices in the subcontinent. Soon, these currents merged with the global ‘mainstream.’ But the story of the merger goes beyond its apparent chronological framework. There has been a history of the aspiration to this effect. That history has seen at least four major turning points.

The first turning point was marked by the historical, political, and aesthetic positioning of the Revivalists. Their quest for the ‘Indian’ and a new ‘modern,’ and for this purpose, their appropriation of the historical, negotiation with the socio-political, and interjection of the personal and a shared subjectivity brought about an aesthetics that revolted against the one that was being programmed and imposed by the British government.

The second turning point was defined by the agenda and aesthetic pursuits of the Progressive artist groups that emerged in the wake of India’s Independence. On one hand, the Progressives were bored with the aesthetic preoccupations of the Revivalists; on the other hand, they were looking to the international and the universal. Indian art was liberated from what was now being considered as conservative ideological dictates. Primacy to ‘significant form’ was asserted for the first time. Barring Souza, most of the Bombay and other Progressives along with other artists of 1940s and 1950s found themselves engaged in focusing on formalism. This was reflected in painting and sculpture alike. While modernism was being redefined with the thrust on formalistic explorations, some ontological departures and interjections took place, e.g. of Amrita Sher-Gill and Souza in whose works the first seeds of the Indian postmodern may be seen.

The third wave of change was brought by the artists from Baroda such as K. G. Subramanyan, Bhupen Khakar, and G. M. Sheikh. The change was perpetuated

Cluster Acrylic on Canvas 2019

Falling Figure Acrylic on Canvas 2009

by artists like Rekha Rodwittiya and Surendran Nair. These artists transformed the rules of the game by shifting the focus away from formalism. Concerns of art history, personal identity vis a vis culture, nation, the world and metaphysical quests were fused to create a new aesthetic regime that Indian art had never earlier witnessed. Intention, intertextuality, symbolism, politics, and gender emerged as raison d’etre of art. Art became loaded with content. Episodes from life, and event and experiences from the surrounding world found place at times within the same work. This approach acquired the nickname of Narravtive School.

The fourth wave of change was brought in early 1990s when Vivan Sundaram abandoned ‘painting’ in favour of the installation; Nalini Malani and Ranbir Kaleka created the first video; M. F. Husain hosted his Swetambari show at Jahangir art gallery, and N. N. Rimzon and Bose Krishnamachari preferred installation over conventional modes of painting or sculpture. The future of Indian art, hence, was changed forever. The rules were dramatically changed. The old baggage of genre-specific art practice, or medium-material oriented pursuits was thrown out the window. A new culture of disorder, a new form of anarchy, conscious positions of disorientations, a new ‘international,’ and fresh questions about the political

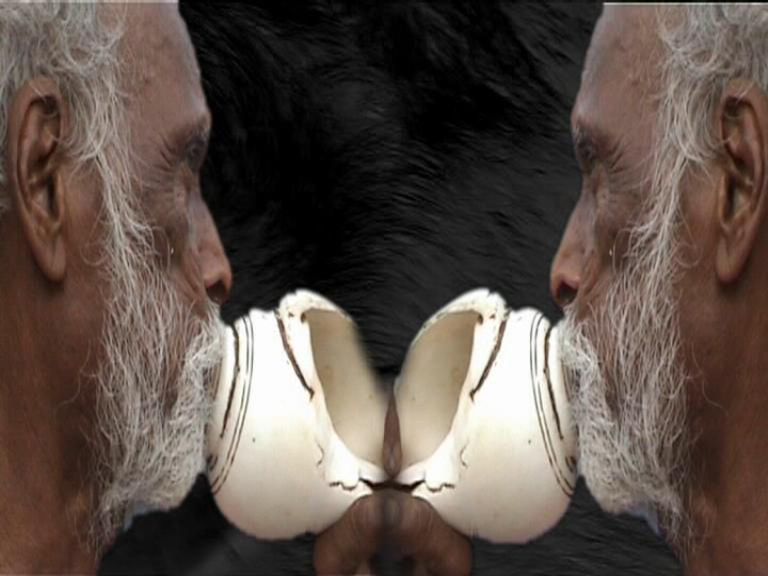

Man with Mask Acrylic on Canvas Dypitch 2009

became central concerns of visual arts. The explosion has been seen in the choice of diverse media, impetus for experimentalism, and exploration of the modes of alternative art practices. An urge, at least theoretical urge, for de-commoditization has come to the centre of the aesthetic praxis. Political reality, modes of discriminations, and violence has become significant themes of artistic engagements.

Intervention from Orissa

While the above turning points are gleaned on pan-Indian level at large, region-specific developments have also maintained parallels. The phenomenon and force of the regional in the creation of the national or the pan-Indian has a dialectical history worth casting a glance.

First, there were artists from Bengal who engineered the first significant change. Then with the rise of the Bombay Progressives, Mumbai became another centre for significant art activity. After the Partition, Delhi Shilpi Chakra provided impetus to art activity in Delhi. Something also started happening in Chennai, Hyderabad, Baroda, and Bangalore. Thus arose the regional force contributing to the variety and richness of India’s visual mosaic. The significance of the rise of such regional centres lay in their ability to yield regional elements and make them part of how Indian modernity was being discussed and analysed. It was no longer possible to define Indian modernity on generalized terms—there was nothing pan-Indian any more as it was witnessed during Revivalism. Not that nothing was happening in U. P., M. P., Rajasthan, Bihar, Orissa, and Kerala, but the mainstream discourse on Indian art has chosen to relegate these states to the margins. One such State is Orissa. Gayatri Sinha has written a major essay on modern Orissan art, although she leaves the contemporaries outside the scope of her essay.[1]

Orissa has seen three generations of artists that define its journey from modernity to post modernity. The first generation artists were contemporary of the Post-Revivalists. Artists like Ajit Keshari Ray[2] who studied in London, Anant Panda (1934- ) who studied at Shanti Niketan (contemporary of Ramkinkar Baij (1904-1980) and whose sculpture is still there), Bipin Bihari Choudhury, and Gopal Kanungo (1904-1971) who is author of Utkalra Citrakala (1964) are almost forgotten.

The Angel Acrylic on Canvas 2009

The second-generation artists are Dinanath Pathy (1941- ), Prafulla Mohanti, and Jatin Das who have been widely noted for their various activities. The position maintained by the Revivalists and Post-Revivalists in the context of forming the pan-Indian modernity is being maintained by Pathy for calibrating his version of modernity from Orissa. The triangular circuit—of the modern, the historical, and the traditional—continues in Pathy’s art albeit with the exception that he does not reject the oil medium like the Revivalists did with regard to oil colour holding it Western. From the perspective of regional modernity, the linguistic and ideological settlement of Pathy is understandable. But we fail to know what significance could be attached to the art of Jatin Das.

Among the third generation of artists are Jagannath Panda, Pratul Das, Suddhanshu Suthar, Tapan Dash, Alok Bal, to name a few. Many of the young turks received encouragement, support, and opportunities from Dinanath Pathy who mentored their formative years in Delhi. Actually, the entry of young turks from Orissa into the mainstream contemporary Indian art was largely engineered by Pathy, a fact many of these very artists are shy to recognize publicly. The present author was witness to the scenario in the nineties when Pathy provided shelter and even subsistence to many young artists from Orissa some of whom are quite famous today. The most noted of the new breed of artists is perhaps Jagannath Panda (1970- ). His work in a recent auction touched a new height of Rs. 1.34 crores.[3] Trained as a sculptor in B. K. College of Art and then at the M. S. U. of Baroda, and Royal College of Art, London attending many residencies later in different countries Panda migrated to painting in the last decade. Recently, however, he has come back to sculpture, as the current trends in Indian and global art demand the making of paintings, sculpture, video, site-specific and other alternative art practices.

[1] Gayatri Sinha, “The Modern Art Movement: Orissa Revisited,” Marg, Pratapaditya Pal (ed.), Vol. 52-53, p. 131-141. More information could be found in Dinanath Pathy, Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom, publisher, year, Delhi.

[2] For details see, Dinanath Pathy (ed.), Ajit Keshari Ray: Portrait of a Painter, Harman Publishing House, Delhi, 2004.

[3] Panda’s Untitled (lot 66) fetched US$ 353,625 in Saffronart’s Spring Online Auction of Contemporary Indian Art, 13 March, 2008. Sudhanshu Sutar’s Untitled (lot 88) was sold for US$ 89125 (Rs. 33.8 lacs) in the same auction making him the second most expensive artist from Orissa. (Source: Saffronart.com, auction results, Sprint Auction 2008 (Mar 12-13, 2008), http://www.saffronart.com/auctions/PostCatalog.aspx?eid=21&sf=QXJ0aXN0SWQ9MjAzNQ%3d%3d-CkXAA4VDuwQ%3d, accessed on April 15, 2009.)

Location of Pratul Dash

Still Images Ek Rabibar Video 2007

Still Life Of Double Video 2008

experimental in nature. Reflection of the international is already a value in itself. The second level of evaluation comes from his artistic concerns. If the act of choosing diverse media of expressions such as painting (fig. 00), sculpture (fig. 00), video art (fig. 00), performance art (fig. 00), photographic art (fig. 00), and nature art (fig. 00) places him in the forefront of the ‘mainstream’ art practice in the global arena, the choice of the subject matter, the content and concerns, speaks of the artist’s subjectivity rooted in the local contexts—the socio-political and cultural milieu in which he lives. The presence of the international is nothing new. In fact, it is a part and parcel of India’s modernity and postmodernity as is partly gleaned from our survey. The presence of the local and the regional is also in line with the prolonged quest of Indian artists to come to terms with the time, space, and locale to which they relate and interact most immediately. The international and the local in fact are tropes, a sort of aporia, in philosophical terms, which Indian artists have been trying to define and redefine since the earliest to the current momentum of Indian arts. Its permeation into the works of artists such as Subodh Gupta, Bose Krishnamachari, Chintan Upadhyay, Ranabir Kaleka, Jagannath Panda, Atul Dodia, Atul Bhalla, to name just a few, is emblematic only of a long-drawn quest which is far from over.

Now let us cast a closer look at Pratul’s works to see where it is positioned. The most dominant feature, perhaps, is the outlook of his pictorial language, which fits within the slot of the so-called Photo-Realism. It is a non-standard loose designation to describe the recent tendency in Indian art found in the vocabulary of a plethora of artists, some very famous, others unknown. Actually, Photo-Realism emerged suddenly in India in the 1990s and spread like an epidemic. Many artists who had well-established vocabulary changed the linguistic position drastically to mount on to the new wagon. Some noted names are Subodh Gupta, Surendran Nair, Shibu Nateshan, T.V. Santosh, Chintan Upadhyay, Jagannath Panda, etc. Somehow, the new vocabulary became immediately successful in communicating its message across to its audience and became a hit in the market. The boom in art industry could not be explained without acknowledging the role of Photo-Realism. Actually, the alienation of art from the masses was substantially reduced after the onset of Photo-Realism. It became a potent language of pictorial expression—the earlier barriers in visual and creative communication were destroyed. Like all movements, this too will die its natural death, but the critics of Photo-Realism must acknowledge its legitimate place in shaping the contemporary ethos and linguistic strategies.

Having thus defined the role of Photo-Realism in contemporary art, we have a parameter from which the art of Pratul dash cannot be dislodged, since it forms the basis of the new pictorial discourse. Opponents of Photo-Realism cry foul, but their problem must relate to one and all—Pratul cannot be singled out. But painting is not the only occupation of Pratul.

Video

Pratul’s videos share a common intertext with his paintings and sculptures. They bear reference to unchecked urban growth leading to deterioration of ecosystem, environment, ecology, climate, and human rights. His signifiers revolve around new construction sites, mushrooming buildings, the chaos of traffic, pollution, consumerist aesthetics, and poor quality of life.

As a character-protagonist in Reflections (2008) he ascends the lifeless staircases of construction sites (fig. 00), and jumps off from the terrace leading to a climactic experience (fig. 00), leaving a suspense in the end for the viewer. It is tragic. Cacophony of traffic is portrayed with aimless wandering by the artist (fig. 00). There is a sense of homelessness, abysmal stairs of construction sites are emblematic of the confusions created by urbanization. The crew of the video includes Anurag Singh and Atul Gupta, noted documentary filmmakers and cinematographers.

The Life of a Double (2007) was performed and filmed on the desolate banks of Hirakut Dam (fig. 00), just outside the artist’s hometown of Burla in Orissa. The janeu (a sacred thread worn by Brahmins) is the main theme. The artist enacts tying his head with the janeu, winding it tightly around his head, so that it gives acute pain to the body. The physical pain is actually suffered and endured in the process of enactment. After several minutes, when the janeu is removed from around his face, the deep marks, the scar-like effects on the face are visible, as a proof of the tormenting, almost torturous marker. These are drawings done on the face, ephemeral in nature, and vanish within ten minutes. A question may be asked. Why has the artist chosen his own janeu, something regarded as so sacred by the one who wears it, and after elaborate ritualistic ceremony? In fact, wearing of a janeu is a rite, a kind of essential sacrament for the Brahmins. Why has the artist selected the janeu to inflict physical pain on the self? Why is the whole thing expressed/enacted in the form of performance, and a site-specific performance? Why is the performance enacted in his hometown at the outskirts of his village? Why is the work site-specific at all? Why is the performance documented as such and presented ultimately as a work of video art? The answer to all these questions lies in the principles of a priori and posteriori as formulated by the great German thinker Immanuel Kant. Knowledge or cognition and experience are of two types. One, which is already existing, outside the person, even before the person has come to know about it. The other kind of knowledge, experience, or entity is what the person comes to know about, out of his or her perception and experience, and which is conditioned by his or her subjectivity. Performance art and video art are now distinct genres of creative expressions—they are a priori in principle. No credit to Pratul dash can be given for the choice of the media or format. But the enactment per se, the interpretation that the janeu, the sacred thread, is emblematic, and a source, of much ethnic strife, intra- and inter-religious conflicts, discrimination between people based on caste and religion—the janeu is not only a sentiment but a symbolic juncture, a fountainhead wherefrom originates much of the hatred plaguing the Indian people. Since the artist himself is a high-caste Brahmin, has been conditioned to wear the janeu since childhood, he is not in a position to disown it, nor to wear it with pride and indifference. It is indeed a source of his intellectual, emotional pain, and political discomfit. The performance hence is largely a posteriori, based on the artist’s subjective experience, which is the anchor-point of originality, creative fountainhead.

Nature Art

Earth – Fear (2008) is a unique work (fig. 00). It is his first work in the category of nature art. There are not many in India who are involved with this genre of creative expressions, although in residencies worldwide, and even in Khoj India similar experiments have been carried out. Nature Art is one of the latest in-thing, which is attracting much critical attention. Once, art was always a part of nature. In fact, much of the folk, tribal, primitive, or traditional aesthetic systems, historically and worldwide, have been connected to nature in a direct way. The nature-culture conflict is not seen much in the traditional societies. The conflict has aggravated since the onset of modernism and industrialization. The formation of mega cities and mega structures has pushed humanity to the brink of isolation from the nature. No wonder, in the era of post-modernism, this negative fallout of Modernism is being reversed, at least theoretically. The modernist promises of man’s emancipation in cities and civilizations have shown itself now as a bottomless pit. The mirage is over. Environmental catastrophe-in-waiting, global warming, climate change, exhausting the earth’s resources, and destruction of eco-systems are some of the by-products of Modernism. It is time now to heal, to get back to nature; arts included. The tender sprouts of wheat that Pratul sown in the backyard of his studio, and the green saplings, in the shape of the letters, “Earth – Fear” are part of the natural response of Post-modernism towards the decadent modernist constructs. The process is most significant in it, which involves the act of farming and gardening.

Sculptures and mannequins

Pratul, trained as a painter, started making small sculptures since 1998. Many of them were actually two identical pieces facing opposite direction but joined in the middle (fig. 00). A variation was a special kind of specs he made that had three glasses instead of the conventional two, the additional glass mimicking the “third eye” (fig. 00). Since 2000, Pratul became engaged with popular imageries and mass media. He walked the streets of Delhi with a camera examining the changing popular aesthetics as in costumes, display signs, interior decorations, but most clearly in the mannequins displayed in the windows of garment shops (fig. 00). This was before the malls started mushrooming in the Indian metropolis. Mannequins embody our sense of idealized beauty. They represent our imagined and collective aesthetics mixed with sexist gaze and desire (fig. 00). The physical characteristics are modelled after the western ideal of beauty and proportion. They are slender and fair. They bear least resemblance with an average Indian woman who is characterized by a rounder form and a pear-shaped body. The aesthetics of the mannequin is no different from those that appear in the media, movies, and beauty pageants – an image that contributes to creating a distorted idea of ‘the perfect female form’ amongst the masses. In a way, the bodies are aimed at drawing commercial gains for business owners as they lure potential customers into a world of fantasy and make-believe. Pratul Dash highlights the problems caused by commoditization of these bodies in the market and the effect that their aesthetics has had on social, cultural, and personal values. Some elements from these aesthetics were incorporated in his later works, which were an amalgam of painting and sculpture as a genre.