Human Spaces

Rajesh K Singh

Solo of Pratul Dash at Sara Khan Contemporary Art, Schaan, Switzerland

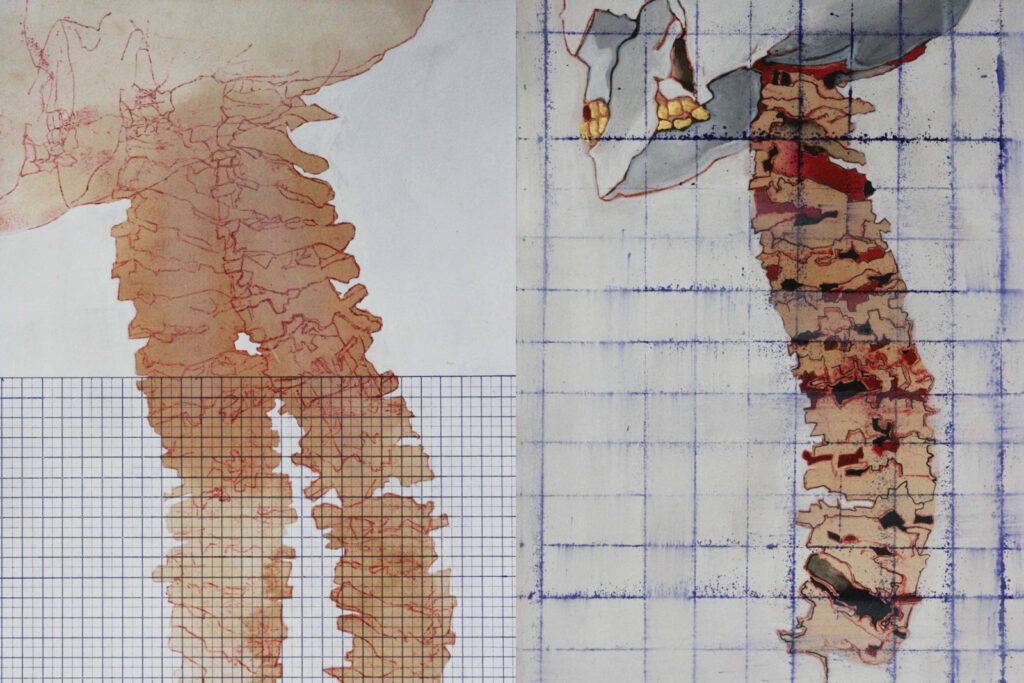

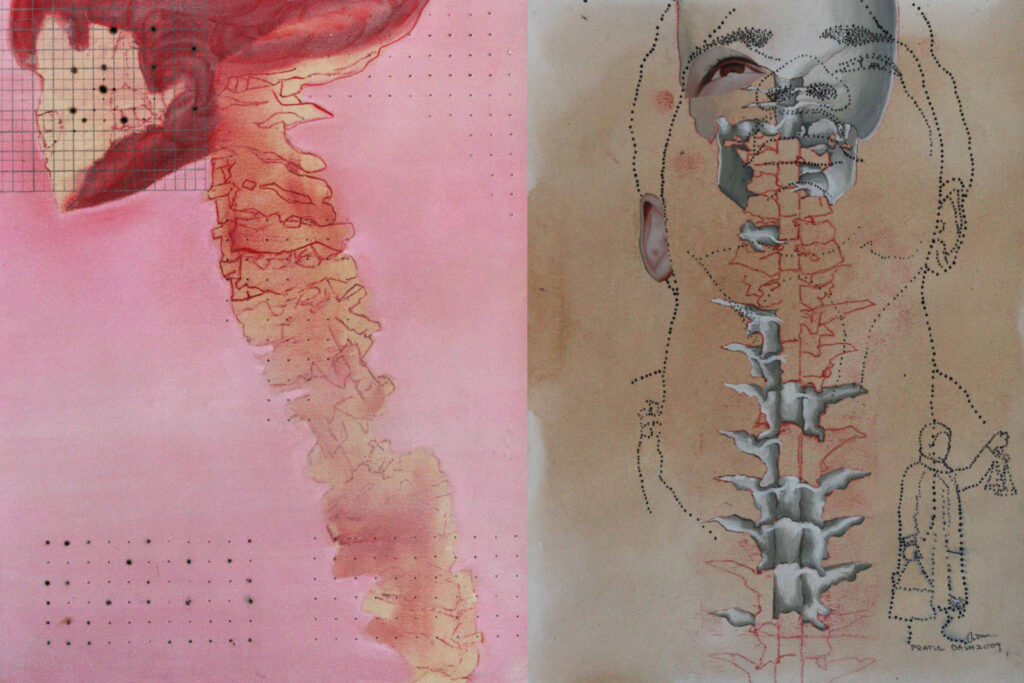

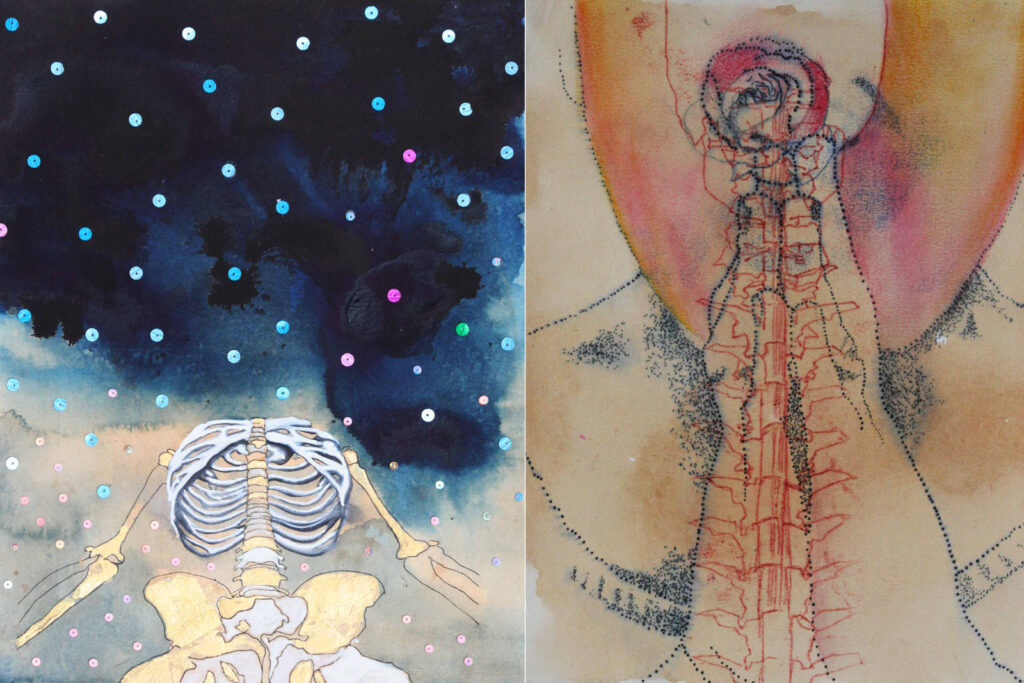

I have had no chance to visit Pratul’s solo show currently on view at Sara Khan Contemporary Art Gallery, Schaan, Switzerland. However, during my last visit to his studio, I had seen the entire range of the works and videos, which are displayed in the show. The current range of works have tangible points to address. Linguistically, there is a marked shift from his earlier style. Some works carry the so-called “photo-realistic” preoccupation (he protests my usage of the term), while the latest paintings seem to be departing away toward a new direction, where brush strokes become more visible, colours richer, and details in focus. This is seen in for instance in the Conch Blower and others in the series.

However, where the subject demands, flat surfaces with fine finish are there, especially in architectural settings. Unending web of walls, floors, corners, openings, and enclosures are spread through the space of large works, which manifest vast architectural spaces―without ceilings―and they are devoid of signs of life. The depictions of signs of life in the form of minimalist vegetation, or human and animal activities do not, intentionally, convey any meaning of substantial presence. The minimalist markers of such presence places the human condition in a strange and ubiquitous context, which is both ironical and self-defeating. The world of the humans, created laboriously by us in the course of centuries is haunting us now. The bird is captured in its own nest!

Such comments and the pictorial semantics partake directly in the act of questioning where we are going. The Copenhagen summit on climate change has just ended, and without any accord; its failure will have implications. Human greed and desire for prosperity at the cost of the presumed others will bite its own tail, the boat of humanity will indeed sink if we don’t mend our ways, if the modernist project is not abandoned, if the philosophy and pattern of growth, at the cost of nature, is not urgently rejected. The larger political and economic debate has its cultural and theoretical counterpart in the form of critical theory, and most eloquently, in the form of ‘pomo’ or post-modernism. While a part of the pomo is classical, revivalist, historical, tribal, cultural, ethnic, and rural―its other dimensions and manifestations incorporate its antagonism with modernism, its critique of the modernist project, its rejection of colonisation, imperialism, logocentrism, homogenising and authoritarian regimes of discourses and practices.

Pomo, of course, is much more than this. But the point is raised here only to suggest that the presence of such anti-modern sentiments in such artworks can not perhaps be explained outside the prevailing ideological, philosophical, and conceptual waves that are conditioning the individual directly, inseparably, and inescapably. Such reflections in art works directly aligns the work with the cross-currents of pomo.

The above reflections are not only found in the gamut of Pratul’s paintings, but also in his videos. Of course, with the spate of video artists emerging by the day and night, it is no longer a sensation to see the next video on a show or forum. Yet the power of the medium, and the peculiar platform of its discourse is such that can not be ignored without careful consideration. No doubt, some works in the name of video art are highly banal in whichever way we judge, yet widespread and rapid popularity of the medium would easily testify its credentials as potent medium of artistic expression and communication.

The latest video The Story of a Landscape screened at Sara Khan Gallery is experimental. It is nothing like we have seen before. The video is unique. The screen shows a landscape, which is none other than a digitally stitched version combining two of the artist’s own paintings, Conch Blower and Man with a Camera. The screen shows the landscape in animation. A migratory bird is flying alone in the sky, then more come flocking. It is a picturesque scene (in the beginning), a torrent flows in the centre of the landscape, one even hears the sounds of the stream flowing through the green meadows and hills. Even a rainbow is visible in distance. Soon, the figure of a human enters the scene from the left. The figure is embedded from a raw footage taken of the artist himself who is performing the role of a photographer, a nature lover, perhaps an academic researcher documenting the flora and fauna, involved in shooting the various details from the scenery; he performs the act of shooting the details from the stream, skies, and hills. The collapsing sound of camera shutter is heard loudly, as we notice garbage-like objects flowing down with the waters. Fishes are seen diving into the air.

As the artist-cameraman exits from the left, there enters from the right a pujari (priest) who pretty soon smells something wrong, as he observes here and there, looks to the skies and birds, for now there is happening a recession of water on the right where a cluster of fish is seen disparate due to the water gradually drying up.

He blows a conch lifting his head toward the sky. While the conch is blowing with a deafening sound, the water is receding further into the ground, and an increasing number of fish is seen dying without water. Finally the water body dries up totally exposing the marine creatures to the harsh scorching sunlight. While the landscape is now getting pale and barren, a lonely flock of geese is seen crossing through the sky; the sounds resembling that of thousands of cicada are heard resounding an impending trouble and doom, as the fish are scorching under the harsh rays of the sun. We never come to know when the landscape is zoomed up, when the greenery is gone, and when a blanket of burnt umber envelops the ominous landscape. It is now, as if, a mine of the dead, a graveyard of dying fish; there is no sign of life any more. An eagle is seen parched in the sky and falling dead to the ground.

Ultimately, the landscape turns black, it looks like a negative film, where nothing is visible; it rather resembles a coal mine now as the sounds of death (inspired from a million cicadas) are growing louder and louder. The crescendo is reached by the last flock of birds disappearing in the dark skies, and the last living fish falls silent.

My five-year old daughter who watched the video with me was so happy initially, and was so upset in the end, her brows had changing expressions, and exclaimed in the end: What happened to the fish? Why is there the skull of an ox lying? Why did the water dry up? Why did they all die? Why has it all turned black?

I wonder if the contents of the video is not really going to translate into reality by the time she reaches my age. I think the power of the video lays in its realism (rather than fantasy) not accepting which may amount to the pelican not willing to see its face in the mirror.